By: Jon Morris

(Senior Analyst, Investment Research)

December 22, 2025

You’ll often hear this phrase from economists or in financial media when discussing issues like housing affordability, inflation or market volatility. Yet, people frequently conflate these concepts; complaints about gas prices, car prices, government spending, tariffs or similar stories from “the economy” are often lumped into reflections on the stock market, despite these themes having an imperfect correlation.

In short: Yes, it’s true, the stock market does not necessarily reflect the economy—but the relationship between the two is a bit more complicated than the phrase implies. Let’s take a closer look to better understand this common phrase.

Understanding the distinction between market-specific and economy-specific effects is always important for monitoring our funds and making informed investment decisions in today’s rapidly evolving environment. I think it’s especially helpful to revisit the idea that “the stock market is not the economy” now because the recent surge in AI-related stock prices has prompted many to ask how market trends reflect—or diverge from—broader economic realities. There are also other prolonged economic trends (including shifts in U.S. wealth creation) playing an increasingly influential role, which I’ll dig into a bit later.

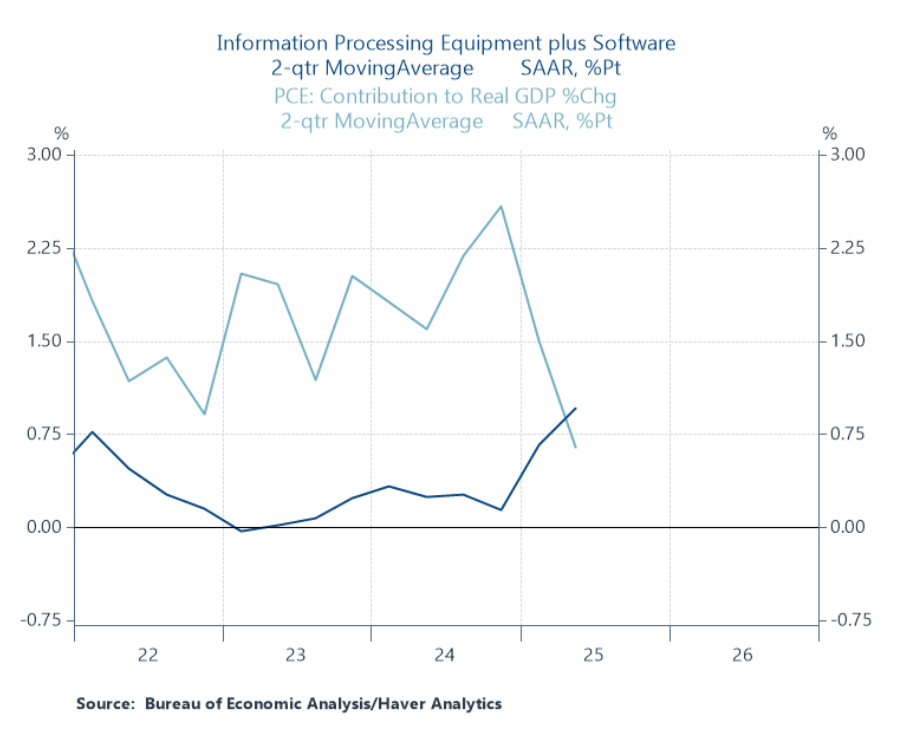

We do see plenty of examples where economic activity correlated with stock market returns. For example, GDP estimates from the Atlanta Fed’s Nowcast point to stronger-than-expected economic growth for 2025, driven largely by private sector investments (specifically, a surge in data center buildouts).

These projects are fueled by corporate enthusiasm for AI, which itself is amplified by public sentiment toward the technology. Meanwhile, just as IT investment related to the build-out of AI has become the driver of economic growth, many AI-related stocks have seen their share prices rise significantly. These stocks are benefitting from both the positive sentiment around AI technology and actual growth driven by higher IT investment rates.

While the stock market’s AI trend shows a recent example of correlation, there are other stories that highlight just the opposite.

For instance, in January 2021, fueled by stimulus checks and pandemic lockdowns, retail investors turned to trading stocks to pass the time. Apps like Robinhood made it fun and easy to trade stocks during the lockdown, contributing to viral stocks like GameStop reaching meteoric heights. While there are economic drivers to what happened to GameStop and other so-called “meme stocks” around this time (stimulus checks, loose monetary policy), the actual economic value of most of these companies (number of stores, revenue, earnings, etc.) didn’t budge. This is a case where the market’s movement wasn’t due to the actual economic drivers of the company.

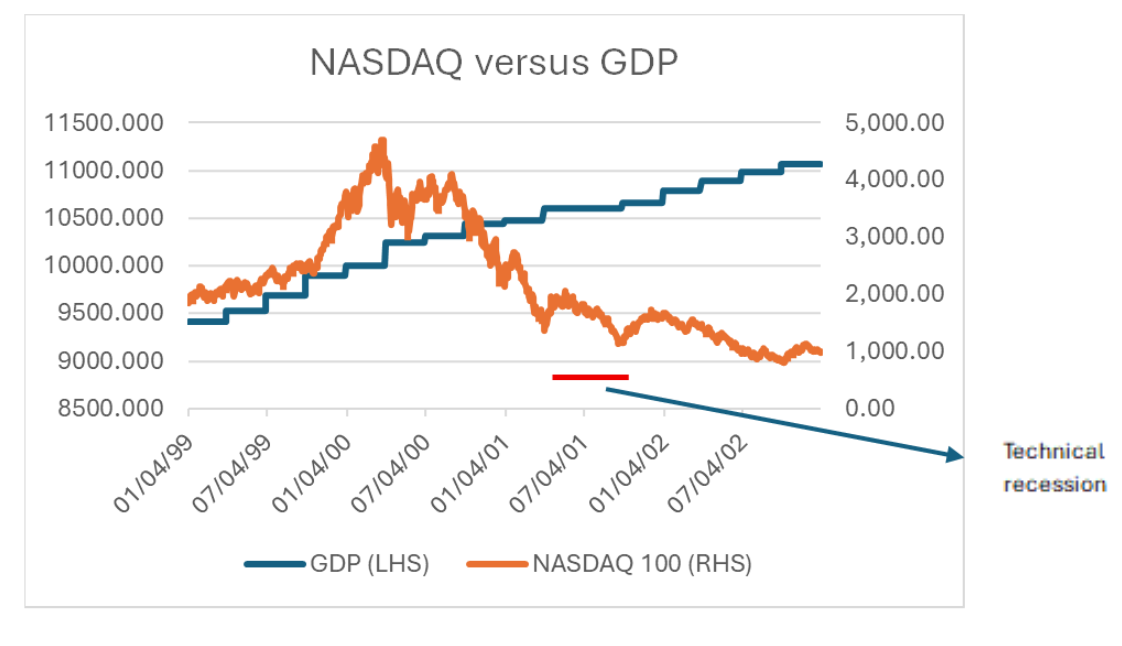

We see another interesting example from the late 1990s and early 2000s. The .com bubble’s extraordinary run-up was met with an almost equally spectacular collapse. In the period between 1999 and 2002, the largest tech companies (as measured by the Nasdaq 100) faced steep investor revaluations, collapsing a staggering -74% as the bubble burst. The drawdowns for names like the still nascent Amazon.com were worse, falling -95% from 1999 to 2001.

One would imagine that such a stunning collapse of the tech darlings would have dragged the U.S. into the depths of a deep recession. But that wasn’t the case. In fact, although the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) classified March through November 2001 as a recession, the country’s GDP barely declined; during those months, GDP grew 2.7% year-over-year as of the second quarter of 2001.

Most economists have called this period a mild downturn that was sector specific rather than full blown collapse. Yes, consumer sentiment fell, and yes, unemployment did rise, but not to levels that reflected the market’s disastrous period. This is a classic case of economic fundamentals differing from market outcomes.

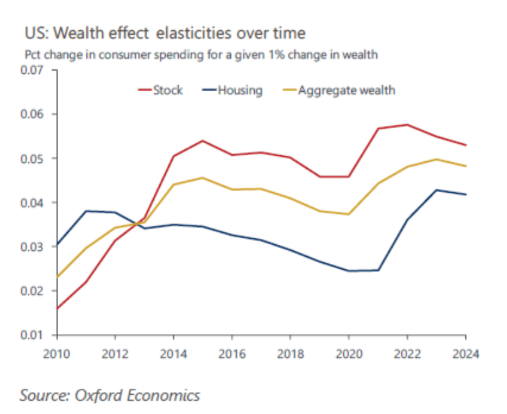

Beyond these historical examples, one can see other interesting areas where there is a systemic connection between the stock market and the economy. For instance, the wealth effect is an important factor that’s experienced meaningful changes in recent years.

The wealth effect is an economic concept wherein the value of household assets, including stocks and real estate, impacts consumer spending and economic activity. While we may think of positive economic activity eventually leading to higher stock markets and home prices, the reverse phenomenon can be true, too. Here’s a look at U.S. wealth effect trends over the past 15 years:

This chart shows the percentage change in consumer spending for a given 1% change in wealth of stocks (red line), housing (blue line) and aggregate wealth (yellow line). What we see is that, while both higher stock prices and higher home prices lift consumer spending, stock prices have a bigger impact. This can be attributed to stock markets recovering quicker than the housing market after the Great Financial Crisis and the past five years being an above-average return period in the market. So, while the stock market may not be the economy, it certainly seems to influence it more than ever.

While wealth effects are not constant, this underlying trend does provide some rationale for this year’s economic narratives: As equity markets recovered from the short-lived bear market in April, spending growth appears to be propped up by rising stocks, helping the economy offset the otherwise volatile backdrop of poor labor market conditions, persistent inflation and heightened policy uncertainty. This understanding helps us better monitor our funds in response to evolving economic dynamics, both today and in the future.

Of course, maintaining disciplined risk management and oversight remains essential, regardless of where we are in the market cycle. We’ll continue to evaluate these types of trends as we remain committed to diligently stewarding assets over the long-term.

We have updated our website with a new look and made it simple to navigate on any device.

We will continue to add more valuable information and features. Please let us know how we are doing.

P.S. For plan sponsors and plan participants, we have a new look for you too. Check out the Wespath Benefits and Investments website.